Attack on etherium smart contracts

One of the most devastating attacks you need to watch out for when developing smart contracts with Solidity are reentrancy attacks. They are devastating for two reasons: they can completely drain your smart contract of its ether, and they can sneak their way into your code if you’re not careful. The hacker exploited a bug in the code of the DAO and stole more or less $50 million worth of ether

Story time

On July 19 2017, a hacker or a group of hackers transferred more than 150K ether from ethereum multi-signature contracts to their account. Furthermore, a group called “White Hat Group” drained over 350K ether following the attack. The white hat group used the same code vulnerability as the hackers did in their attack and claimed on reddit to return the drained ether after getting compensated by DAO for gas cost – whether it will happen remains to be seen.

Basic concepts

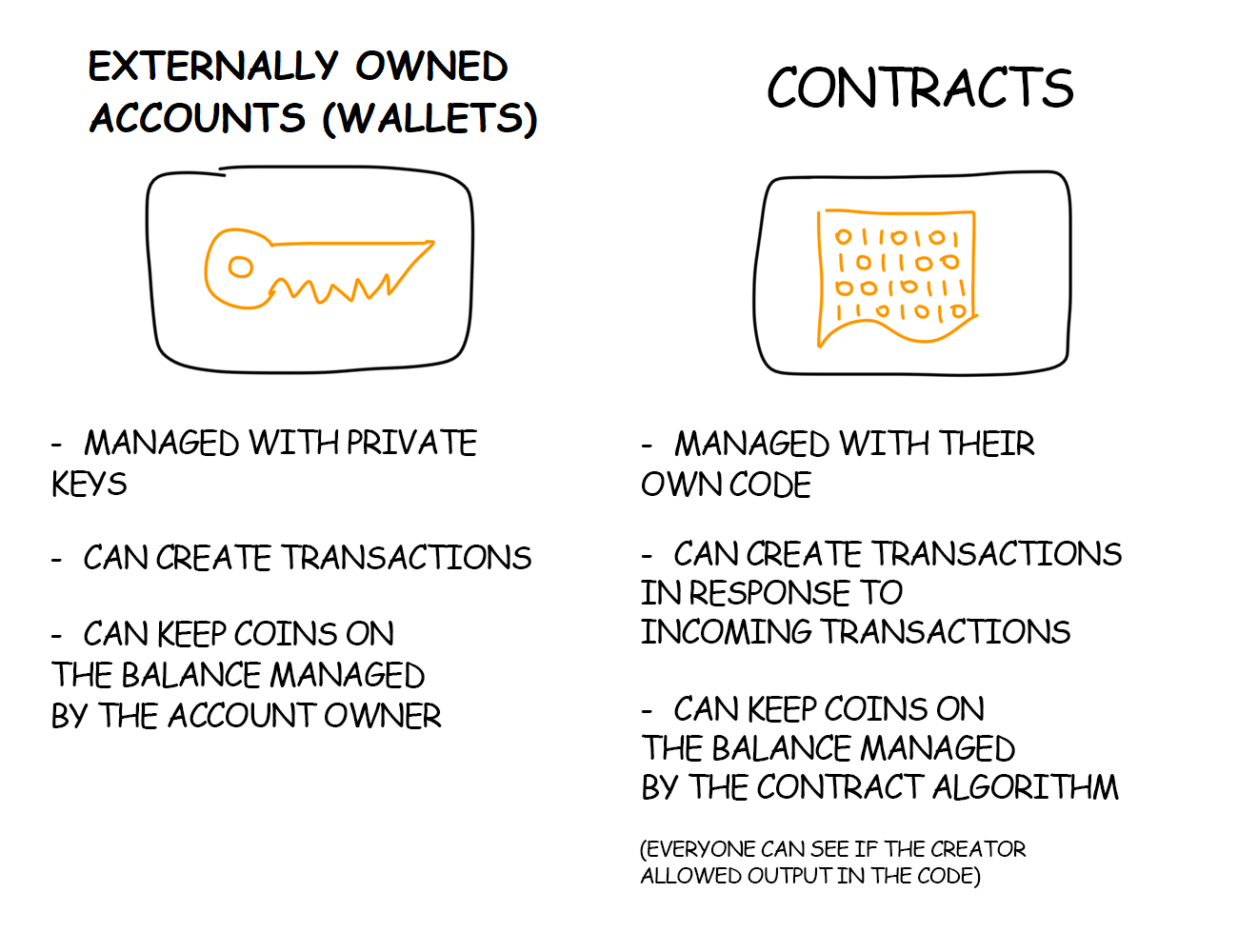

In Ethereum there are two types of accounts:

- externally owned accounts controlled by humans and

- contract accounts controlled by code.

This is important because only contract accounts have associated code, and hence, can have a fallback function.

In Ethereum all the action is triggered by transactions or messages (calls) set off by externally owned accounts. Those transactions can be an ether transfer or the triggering of contract code. Remember, contracts can trigger other contracts’ code as well.

Solidity supports three ways of transferring ether between wallets and smart contracts. These supported methods of transferring ether are send(), transfer() and call.value().

A contract can have at most one receive function, declared using receive() external payable { … } (without the function keyword). This function cannot have arguments, cannot return anything and must have external visibility and payable state mutability. It is executed on a call to the contract with empty calldata. This is the function that is executed on plain Ether transfers (e.g. via .send() or .transfer()). If no such function exists, but a payable fallback function exists, the fallback function will be called on a plain Ether transfer. If neither a receive Ether nor a payable fallback function is present, the contract cannot receive Ether through regular transactions and throws an exception.

Attack

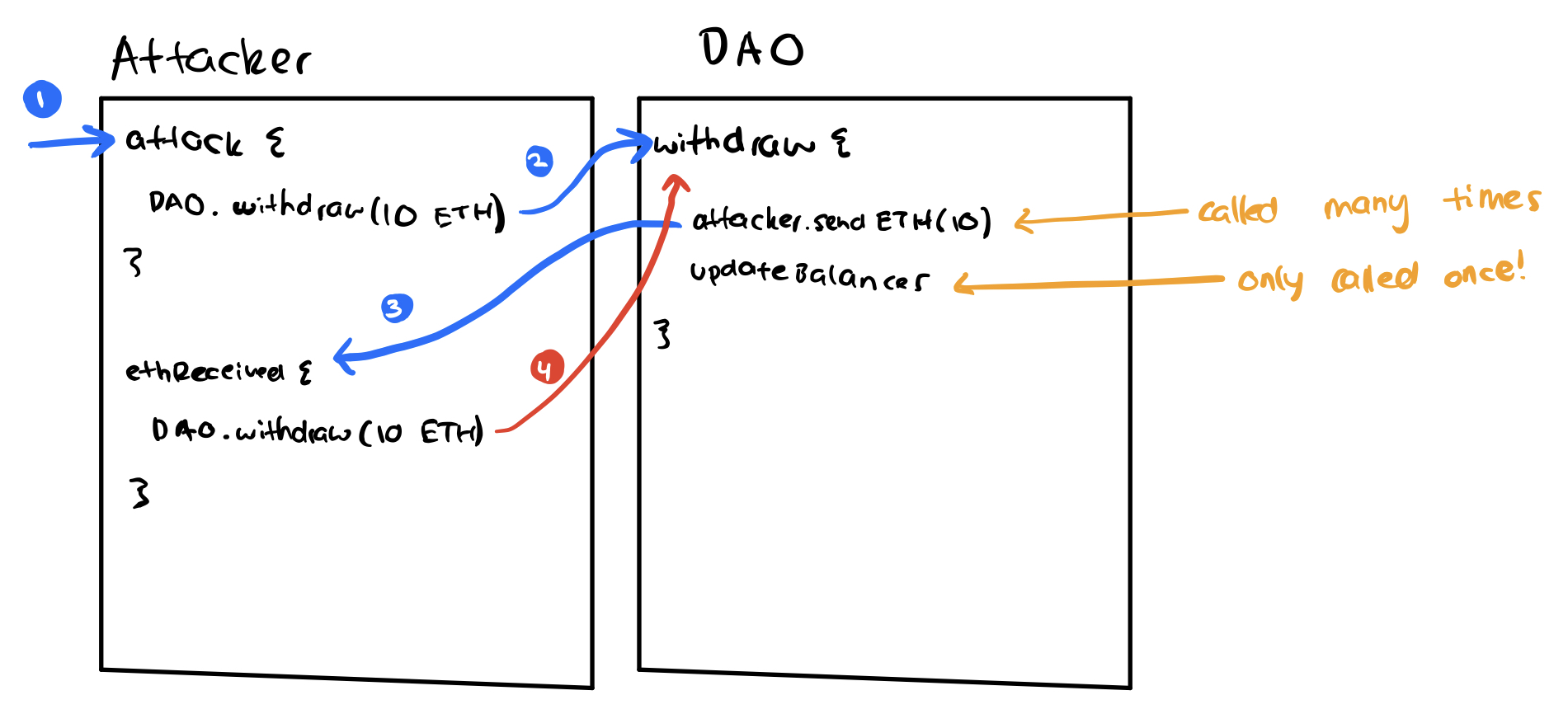

The fallback function abuse played a very important role in the DAO attack. Let’s see what a fallback function is and how it can be used for malicious purposes.

Fallback function

A contract can have one anonymous function, known as well as the fallback function. This function does not take any arguments and it is triggered in three cases :

- If none of the functions of the call to the contract match any of the functions in the called contract

- When the contract receives ether without extra data

- If no data was supplied

Types of reentrancy attacks

1. Single function reentrancy attack

This type of attack is the simplest and easiest to prevent. It occurs when the vulnerable function is the same function the attacker is trying to recursively call.

-

The attacker creates a contract which he executes the attack from. This contract has two functions. One to withdraw ETH from the DAO, the second that is called when ETH is received (standard part of any Solidity contract)

-

The contract calls the withdraw function and the first line of the withdraw function is to send the ETH to the person who requested the withdrawl

-

Since the requester is the contract and can call a function when it receives ETH, it then in turn calls the withdraw function on the DAO contract again!

-

He keeps repeating this until his balance is updated at the end, but only for 1 withdrawal, not the amount of ETH he actually withdrew!

2. Cross-function reentrancy attack

These attacks are harder to detect. A cross-function reentrancy attack is possible when a vulnerable function shares state with another function that has a desirable effect for the attacker.

function transfer(address to, uint amount) external {

if (balances[msg.sender] >= amount) {

balances[to] += amount;

balances[msg.sender] -= amount;

}

}function withdraw() external {

uint256 amount = balances[msg.sender];

require(msg.sender.call.value(amount)());

balances[msg.sender] = 0;

}

In this example, withdraw calls the attacker’s fallback function same as with the single function reentrancy attack. The difference is the fallback function makes a call to transfer instead of recursively calling withdraw. Because the balance has not been set to 0 before this call, the transfer function can transfer a balance that has already been spent.

This vulnerability was also used in the DAO attack.

The DAO Attack of 2016

Attackers used a combination of these two types of Reentrancy Attacks: Single Function & Cross Function.

The attackers were able to siphon 3.6 Million Ether from the DAO Smart Contract to their own accounts. Fortunately, the Ethereum community decided to Hard Fork and restored all the funds to the original Smart Contract. However, this led to a lot of controversy and led to the infamous Ethereum and Ethereum Classic network split.

Up to today, Ethereum bears the stain of the DAO controversy – albeit fading with time. It would be a disaster if it were to happen all over again.

Integer Overflow and Underflow

Here is an example of simple token transfer.

mapping (address => uint256) public balanceOf; // INSECURE function transfer(address _to, uint256 _value) { /* Check if sender has balance */ require(balanceOf[msg.sender] >= _value); /* Add and subtract new balances */ balanceOf[msg.sender] -= _value; balanceOf[_to] += _value; } // SECURE function transfer(address _to, uint256 _value) { /* Check if sender has balance and for overflows */ require(balanceOf[msg.sender] >= _value && balanceOf[_to] + _value >= balanceOf[_to]); /* Add and subtract new balances */ balanceOf[msg.sender] -= _value; balanceOf[_to] += _value; }

If a balance reaches the maximum uint value (2^256) it will circle back to zero which checks for the condition. This may or may not be relevant, depending on the implementation. Think about whether or not the uint value has an opportunity to approach such a large number. Think about how the uint variable changes state, and who has authority to make such changes. If any user can call functions which update the uint value, it’s more vulnerable to attack. If only an admin has access to change the variable’s state, you might be safe. If a user can increment by only 1 at a time, you are probably also safe because there is no feasible way to reach this limit.

The same is true for underflow. If a uint is made to be less than zero, it will cause an underflow and get set to its maximum value.

Be careful with the smaller data-types like uint8, uint16, uint24…etc: they can even more easily hit their maximum value.